The Italian Renaissance and Baroque periods stand as towering epochs in the annals of art history, times when genius flourished and the world bore witness to an unparalleled artistic evolution. The Italian Renaissance, which spanned roughly from the 14th to the late 16th century, was a period where the thirst for knowledge and the celebration of human achievement were paramount. This cultural movement revived interest in the Classical art and literature of Ancient Greece and Rome. Churches, palazzos, and public spaces became the canvases on which masterpieces unfolded, capturing the essence of human potential and the divine.

Enter the Baroque era, which ran from the late 16th century to the mid-18th century. This was a time of intense emotion, dramatic expressions, and a heightened sense of realism in art. The Baroque style was characterized by its opulent and exaggerated forms, dynamic compositions, and play of light and shadow. It was more than just an artistic style; it was a reflection of the social, political, and religious tensions of the time.

Amidst this backdrop of artistic fervor, a luminary emerged who would leave an indelible mark on the canvas of art history – Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. Known simply as Caravaggio, this prodigious painter brought a revolution to the realm of sacred art. Unlike many of his contemporaries who painted ethereal and idealized versions of religious figures, Caravaggio’s subjects were raw, real, and deeply human. His use of intense naturalism combined with dramatic lighting not only highlighted the vulnerabilities and emotions of his subjects but also made them relatable to the common man. In doing so, Caravaggio didn’t just paint biblical scenes; he breathed life into them, presenting narratives that were tangible and deeply moving.

As we journey through the divine beauty in Italian painting, it becomes imperative to delve into the world of Caravaggio – a master who not only mirrored the society he lived in but also profoundly influenced the generations of artists that followed.

Background of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Born in the small Lombard town of Caravaggio in 1571, Michelangelo Merisi was destined to become one of the most influential figures in the world of art. However, his beginnings were humble. The son of Fermo Merisi, a mason and architect, and Lucia Aratori, the young Michelangelo faced the grief of losing his father and grandfather in the same year when he was just six years old due to the bubonic plague.

Early Life and Artistic Training

Growing up, Caravaggio moved to Milan, where he began his artistic journey under the tutelage of Simone Peterzano, a painter who claimed to be a disciple of Titian, one of the foremost Venetian Renaissance painters. This period in Milan was crucial for young Caravaggio, offering him a foundation in the techniques and traditions of painting, especially those of the Lombard and Venetian schools.

In his early twenties, seeking both fortune and further artistic development, Caravaggio moved to Rome, the epicenter of art and religion. Rome was not kind to him initially. Struggling with poverty, he worked at various workshops, producing low-paid commissioned works. However, fortune favored him when he entered the household of Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte, a significant patron of the arts. Under the Cardinal’s patronage, Caravaggio began to receive more substantial commissions, which not only provided financial stability but also a platform to showcase his unique style.

Defining Characteristics of Caravaggio’s Style

Caravaggio’s artistry is notable for several distinctive features:

Naturalism: Caravaggio had an uncanny ability to capture reality in its rawest form. His subjects, whether divine or mortal, were represented with all their inherent flaws, imperfections, and humanity.

Chiaroscuro: Perhaps his most famous technique, Caravaggio’s use of chiaroscuro (the contrast of light and dark) was revolutionary. His dramatic illumination intensified the emotional depth of his subjects, drawing the viewer into the narrative.

Realism: Rejecting the Mannerist style prevalent in his time, which often portrayed elongated figures in complex poses, Caravaggio chose to depict his subjects in more relatable and realistic scenarios. This approach made biblical and mythological stories more accessible and resonant.

Emotion: His characters aren’t just figures on a canvas; they’re embodiments of raw emotion. Whether it’s the profound sorrow in the eyes of the Virgin Mary or the shocking revelation of the disciples in “The Supper at Emmaus,” Caravaggio’s subjects radiate palpable feelings.

In essence, Caravaggio’s style was a bold departure from the conventions of his time. His unapologetic portrayal of reality, combined with his masterful play of light and shadow, ensured that his works weren’t just paintings; they were experiences. Through his canvas, he invited viewers to not just see but to feel, to question, and to reflect.

Caravaggio’s Role in Defining Sacred Art

The corridors of time are adorned with countless artists who have portrayed the divine, yet few have done so with the audacity and rawness of Caravaggio. To understand his indelible mark on sacred art, it’s crucial to first delve into the landscape of the Italian Renaissance and Baroque periods.

The Significance of Sacred Art during the Italian Renaissance and Baroque Periods

In the wake of the Renaissance, art underwent a transformative rebirth. With the rediscovery of classical art, culture, and philosophy, artists sought to merge the divine with the human, to bring celestial stories to earthly recognition. Churches and chapels were adorned with frescoes and canvases, narrating Biblical tales with a newfound fervor. This was not just about devotion; it was a confluence of faith and the human experience, a testament to the belief that divinity was intricately woven into the fabric of daily life.

The Baroque period, emerging as a response to the Protestant Reformation, saw the Catholic Church leverage art as a powerful tool for the Counter-Reformation. Here, art wasn’t just an aesthetic pursuit; it was an instrument of religious propaganda. The Church commissioned works that would evoke profound emotions, hoping to reclaim the hearts and minds of the masses. Sacred art was not only ornamental but also educational and evangelical.

Caravaggio’s Unique Approach to Depicting Biblical Subjects

Amidst this artistic and religious maelstrom, Caravaggio emerged, challenging and transforming the paradigms of sacred representation. Here’s how:

Humanizing the Divine: While many of his contemporaries were engrossed in idealizing religious figures, Caravaggio chose authenticity. His saints, apostles, and even the Virgin Mary were grounded, flesh-and-blood individuals, often modeled after common people or even the marginalized of society.

Narrative Intensity: Caravaggio’s scenes were not passive retellings but intense snapshots of pivotal moments. His rendition of biblical tales captured the exact second of realization or climax, drawing viewers into the heart of the story.

Use of Everyday Settings: His backgrounds lacked the grandeur or ethereal quality often associated with religious paintings. Instead, they showcased relatable settings – local taverns, simple rooms, or dimly lit streets – making the divine narratives feel close and personal.

Shadow and Light: Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro wasn’t just a stylistic choice; it was a theological one. The stark contrast between the illuminated and the obscure echoed the eternal battle between good and evil, salvation and sin.

Through his unorthodox techniques and vision, Caravaggio made the sacred accessible, relatable, and deeply human. In doing so, he not only redefined sacred art of his era but also laid a foundation that countless artists would build upon in centuries to come.

Key Masterpieces

Caravaggio’s oeuvre is vast and varied, but a few of his masterpieces stand out, not only for their technical brilliance but also for the profound narratives they encapsulate. Let’s delve into some of these iconic works:

The Calling of Saint Matthew

Description and Artistic Significance:

Housed in the San Luigi dei Francesi church in Rome, “The Calling of Saint Matthew” portrays the transformative moment when Christ, entering a dimly lit tax collector’s office, summons Levi (later Saint Matthew) to follow Him. Caravaggio masterfully juxtaposes the divine figure of Christ against the mundane setting of the tax office, emphasizing the unexpected intersections of the divine and everyday life.

Clever Use of Light and Shadow:

The room is dominated by shadows, but a brilliant shaft of light beams down on Saint Matthew. This light, representing divine intervention, not only illuminates Matthew but also metaphorically calls him out of spiritual darkness. Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro here is more than technique; it’s a profound narrative tool.

The Supper at Emmaus

Insights into its Composition and the Emotions it Evokes:

This painting captures the instant the resurrected Christ reveals His identity to two of His disciples at an inn. Their astonishment and realization are palpable. Caravaggio’s rendition is not of a serene, ethereal Christ but of a tangible, present figure, emphasizing His true human form post-resurrection.

How it Diverges from Traditional Depictions:

Traditionally, this biblical event is portrayed in a serene, calm setting. Caravaggio, however, injects it with dynamism. The startled reaction of the disciples, the overturned chair, and the bursting fruit basket create a sense of movement and urgency, a far cry from the static depictions of yore.

Judith Beheading Holofernes

Intense Realism and the Story Behind the Scene:

This is Caravaggio at his most graphic. The painting depicts the biblical heroine Judith decapitating the Assyrian general, Holofernes. The rawness of the act, the blood spewing, Judith’s grim determination, and Holofernes’ shock and pain are viscerally portrayed. This isn’t just a religious scene; it’s a stark snapshot of courage, brutality, and sacrifice.

Other Notable Works in the Realm of Sacred Art:

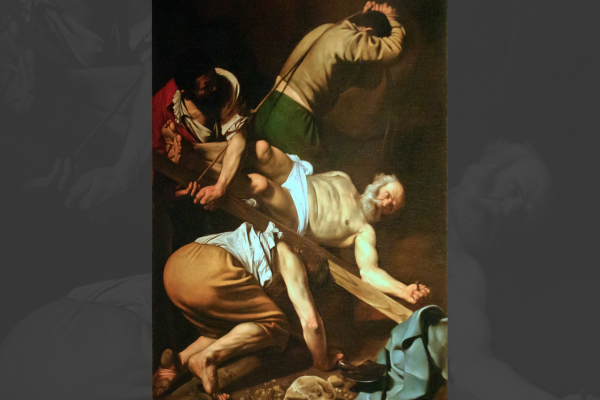

“The Crucifixion of Saint Peter”: This masterpiece showcases Saint Peter being crucified upside down, a haunting portrayal of sacrifice and martyrdom.

“The Entombment of Christ”: Here, Caravaggio paints the somber moment Christ’s body is laid in the tomb, capturing the raw grief of His followers.

“The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula”: One of his last works, this painting illustrates the moment Saint Ursula is struck by an arrow, emphasizing her courage and faith.

Each of Caravaggio’s masterpieces is a narrative gem, blending technique, emotion, and storytelling in a manner few artists have ever achieved.

The Influence of Chiaroscuro

The term ‘chiaroscuro’ might seem exotic, but its impact on art is nothing short of transformative. This technique, characterized by the pronounced use of light and shadow, found its most iconic proponent in Caravaggio. His mastery over chiaroscuro didn’t just shape his works but also cast a long, influential shadow over art history.

Explanation of the Chiaroscuro Technique:

Derived from the Italian words ‘chiaro’ (light) and ‘scuro’ (dark), chiaroscuro refers to the use of strong contrasts between light and dark to give the illusion of volume in modeling three-dimensional objects and figures. More than just a technique, chiaroscuro is an artistic language that plays with viewer perceptions, creating depth, volume, and spatial relationships in two-dimensional artworks.

How Caravaggio Mastered and Popularized this Style:

While the roots of chiaroscuro can be traced back to the Renaissance period with artists like Leonardo da Vinci utilizing it to a degree, it was Caravaggio who truly embraced and intensified this technique. His works didn’t just feature contrasts; they were dominated by them.

Caravaggio’s application was bold – illuminating specific parts of his canvas with almost theatrical lighting while plunging others into deep shadow. This not only created dramatic effects but also directed the viewer’s focus, ensuring they were drawn to the narrative’s emotional core.

His undeniable proficiency turned chiaroscuro from a mere technique into a movement, leading to the emergence of “Caravaggisti” or followers of Caravaggio across Europe, who emulated his striking style.

Its Role in Enhancing the Drama and Emotional Intensity of Sacred Scenes:

For Caravaggio, chiaroscuro was more than a play of light and dark; it was a medium to convey the emotional and spiritual intensity of his scenes. In his sacred works, the pronounced contrasts often served a theological purpose:

Divine Illumination: In paintings like “The Calling of Saint Matthew,” the light can be seen as the divine call itself – an intervention from above that seeks to pull souls out of the shadows of ignorance or sin.

Emotional Amplification: Scenes like “Judith Beheading Holofernes” use the stark interplay of light and shadow to heighten the emotions – the horror, the determination, the brutality.

Focus on the Mundane: By casting everyday subjects in sharp relief against dark backgrounds, Caravaggio elevated the ordinary to the extraordinary, reminding viewers of the divine’s constant presence in the mundane.

Through his pioneering use of chiaroscuro, Caravaggio didn’t just paint scenes; he sculpted emotions, creating works that were immersive, intense, and profoundly moving.

The Controversies Surrounding Caravaggio’s Depictions

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, in his tumultuous life, was not just a trailblazing artist; he was also a magnet for controversy. His daring interpretations of religious subjects, coupled with his radical stylistic choices, often set him at odds with prevailing norms and expectations. Let’s delve into the upheavals his artistry triggered:

How His Unidealized, Raw Portrayals Often Clashed with Church Expectations:

Divine Made Human: The Italian Renaissance and the ensuing Baroque period were eras of embellished ideals, with most artists portraying religious figures in a manner that elevated them above mere mortals. Caravaggio, in contrast, grounded his subjects. His saints bore the weathered faces of everyday Romans, his Madonnas the visages of common women. Such depictions, while evoking a more relatable form of spirituality, were not always welcomed by the Church, which sought grandeur and elevation in religious imagery.

Graphic Realism: Caravaggio’s penchant for depicting scenes in their stark reality – be it the visceral brutality in “Judith Beheading Holofernes” or the raw emotion in “The Entombment of Christ” – sometimes ruffled ecclesiastical feathers. His refusal to shy away from the blood, sweat, and tears of these narratives made many within the Church uncomfortable, feeling that such rawness detracted from the sanctity of the subjects.

Use of Questionable Models: Caravaggio often employed prostitutes, beggars, and other marginalized individuals as models for his sacred paintings. Such choices, while underscoring his commitment to authenticity, were scandalous to many, especially when viewers recognized the faces from the streets of Rome immortalized as saints and angels.

Public and Critical Reception During His Time:

Divided Opinions: Caravaggio’s work elicited strong reactions, both of admiration and disdain. While some hailed him as a genius who breathed new life into religious art, others saw him as a renegade, whose unorthodox methods bordered on blasphemy.

Celebrity and Infamy: His undeniable talent led to a steady stream of commissions, making him one of Rome’s most sought-after artists. However, his personal life – marked by brawls, legal issues, and a notorious murder charge – further fueled his controversial reputation.

The Caravaggisti Effect: Despite the controversies, or perhaps because of them, Caravaggio amassed a band of followers, known as the Caravaggisti. These artists, spread across Europe, were profoundly influenced by his style, ensuring that his legacy, and with it the debates surrounding his approach, lived on.

Caravaggio’s journey was one of constant tension between his revolutionary vision and the traditions of his time. While he may have been a polarizing figure, he undeniably reshaped the landscape of religious art, challenging conventions and provoking thought in ways few artists had dared.

Legacy and Influence

Caravaggio’s journey through art history is one of profound influence and enduring legacy. While he may have lived a tumultuous life, often mired in controversy, his artistic contributions resonate powerfully to this day. From breaking conventions to inspiring generations, Caravaggio’s legacy is a testament to his genius.

How Caravaggio’s Work Paved the Way for Later Artists:

Birth of the Baroque: Caravaggio’s intense chiaroscuro and raw emotionalism can be seen as the bedrock upon which the Baroque movement was built. His dramatic use of light and shadow, combined with his emotional depth, set the stage for the grandeur and expressiveness that characterized Baroque art.

The Caravaggisti Movement: Beyond Italy, Caravaggio’s influence spread across Europe, spawning a legion of followers known as the Caravaggisti. Artists like Orazio Gentileschi, Georges de La Tour, and Gerrit van Honthorst, among others, were deeply influenced by his style, disseminating his techniques and thematic boldness across borders.

Inspiration for Modern Realism: Fast forward to the 19th and 20th centuries, and Caravaggio’s commitment to realism and his unfiltered portrayal of human experiences can be seen as precursors to the Realist and even the Neorealism movements. His influence is evident in the works of artists such as Édouard Manet, who often sought to depict life as it truly was, without embellishment.

His Lasting Impact on the Depiction of Religious Subjects in Art:

A Touch of the Real: Prior to Caravaggio, religious art often hovered in the realm of the idealized and ethereal. He brought it down to earth, rendering biblical figures as tangible, relatable beings, making religious narratives more accessible and emotionally resonant to everyday viewers.

Emotional Depth: Caravaggio’s works aren’t just visual masterpieces; they’re deeply emotional narratives. This emotional depth transformed religious art from mere illustrative depictions to profound explorations of faith, doubt, sacrifice, and redemption.

Redefining Sacredness: By employing people from all walks of life, Caravaggio challenged societal perceptions of sanctity. He posited that the divine could be found in the most unexpected places and faces, a radical notion that expanded the boundaries of religious art.

In the annals of art history, Caravaggio stands as a titan, a revolutionary whose work transcended his era, continually inspiring and challenging artists and audiences alike. His legacy is not just in the canvases he left behind, but in the evolving landscape of art that he irrevocably altered.

The Divine Beauty in Context

The notion of “divine beauty” in art has been a subject of meditation for artists, theologians, and philosophers alike. It’s an elusive ideal, a confluence of the ethereal with the tangible, often captured in art as an exalted form of beauty that transcends the mundane. Caravaggio, in his bold and innovative style, provided a fresh perspective on this timeless concept, inviting audiences to engage with divinity on a profoundly human level.

A Reflection on the Essence of “Divine Beauty” in Art

Historical Context: Historically, “divine beauty” in religious art was often synonymous with perfection, serenity, and otherworldliness. It sought to elevate subjects beyond the terrestrial realm, showcasing them as ideals rather than entities of flesh and blood.

Intrinsic Vs. Representational: The beauty in such works is both intrinsic, derived from the subjects themselves (like saints or deities), and representational, stemming from the artistic techniques employed to portray an aura of sanctity.

How Caravaggio’s Works Challenge and Redefine this Concept

Humanization of the Divine: Caravaggio’s groundbreaking approach lay in his portrayal of religious figures as palpably human. His saints and apostles bear the marks of lived lives — wrinkles, blemishes, and expressions of genuine emotion. This humanization, rather than diminishing the divine beauty, made it more accessible and immediate, bridging the gap between the mortal and the eternal.

Chiaroscuro as a Metaphor: Caravaggio’s signature use of light and shadow wasn’t just a stylistic choice. It can be seen as a metaphor for the interplay of the divine and the human. The sharp contrasts symbolize the coexistence of godliness and humanity, light and darkness, elevating the everyday to the realm of the sacred.

Reimagining Sanctity: By casting ordinary people, often from society’s margins, as his divine subjects, Caravaggio challenged traditional notions of sanctity. His “divine beauty” is found not in idealized perfection but in raw authenticity, suggesting that the sacred can be found in the most ordinary of places and faces.

Emotion as a Window to the Divine: Caravaggio’s works are replete with raw, unfiltered emotion, from Mary’s anguish in “The Deposition” to Matthew’s awe in “The Calling of Saint Matthew”. These profound emotions provide a direct, visceral connection to the divine, redefining divine beauty as something deeply felt rather than just seen.

In conclusion, Caravaggio’s contributions to art transcended mere technique or style. He offered a profound philosophical shift in how we perceive divine beauty. By grounding the sacred in the real, the extraordinary in the ordinary, he invited viewers to experience divinity not as a distant ideal but as a tangible, immediate presence.

Conclusion

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, a name that once echoed through the streets of Rome with a mix of admiration and scandal, has left an indelible mark on the canvas of art history. His pioneering approach to sacred art, steeped in raw emotion and daring realism, offers more than just visual grandeur; it opens a dialogue on the essence of divine beauty and how we relate to it.

The Timeless Allure of Caravaggio’s Sacred Art

Realism Meets Reverence: Caravaggio’s genius lies in his ability to blend gritty realism with profound reverence. His sacred subjects, with their tangible humanity, invite viewers into a personal, intimate encounter with the divine. This unique blend makes his works as impactful today as they were in the 17th century.

Emotion as a Bridge: Art, at its best, moves the soul. Caravaggio’s pieces are potent emotional journeys, traversing the landscapes of faith, doubt, hope, and redemption. This emotional depth ensures that his paintings, regardless of shifting artistic trends, remain timeless in their allure.

His Profound Influence on How We Perceive Divine Beauty in Art Today

Breaking the Mold: Caravaggio’s audacious choices, from his models to his use of light, shattered prevailing notions of what constituted ‘divine beauty.’ In doing so, he expanded the palette with which artists could explore and express the sacred.

Legacy of Perspective: Contemporary artists, whether they draw direct inspiration from Caravaggio or not, owe a debt to his perspective. Today’s diverse interpretations of divine beauty, which embrace a broad spectrum from the abstract to the hyper-realistic, find their roots in Caravaggio’s trailblazing approach.

A Beacon for Modern Spirituality: In an era where spirituality is increasingly personal and eclectic, Caravaggio’s works resonate powerfully. They remind us that the divine is not just found in celestial realms but is interwoven with the fabric of our everyday lives.

As we step back and admire the vast tapestry of sacred art, Caravaggio’s contributions stand out, not just as masterpieces of visual art but as profound meditations on the nature of the divine. His legacy is a testament to art’s power to challenge, inspire, and transform, continually reshaping our understanding of what it means to perceive and portray the sacred.